Bennie Jordan sits outside the Student Rec Center collecting signatures for a petition to lower the cost of living.

Bennie Jordan, clad in a Golden State Warriors beanie and a blue puffer jacket, sat at a table nestled between bike racks outside of the Student Rec Center, inviting people to “SIGN HERE if the cost of living is TOO DAMN HIGH.”

It was a rainy afternoon in mid-January, and Jordan was visiting the University of Oregon as part of his job as a petition promoter. But despite being there for work, he was quick to share other, more personal details about himself.

“My story’s deep,” he says.

Bennie is 66 years old, born in 1956, and has a family history intertwined with centuries of racism in America. His grandmother, Josie Jordan, was born enslaved. His grandfather, James Jordan, was killed in the Tulsa Race Massacre on June 1, 1921, when 35 city blocks of the affluent Black community known as the Greenwood District were left looted, charred and destroyed by white rioters in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Three hundred people were murdered, thousands were left homeless and almost $100 million in property was burned.

James had property on Black Wall Street. He died when his building was bombed by the white mob that took to the streets that day.

Bennie Jordan is now older than his grandfather ever was.

The Massacre “definitely affected generations of people, including myself,” Bennie says.

“Homes, businesses, and community structures including schools, churches, a hospital, and the library were looted and burned or otherwise destroyed.”

He thinks his parents were traumatized by the experience of the Massacre. Bennie says his older relatives made a point not to talk about the brutal nature of James’ death, and they shut down questions about it from Bennie and his cousins. They believed “children should be seen and not heard,” Bennie says.

Though Bennie is based in Stockton, California, he travels all over the country for his work collecting signatures for petitions. He is happy to share his story with anybody who cares to listen, and in a way, is sowing the seeds of information across America.

The events of the Tulsa Race Massacre were not taught in Oklahoma schools for decades, but are currently part of the statewide curriculum and are included on statewide tests. Officials assure that this will not change with Oklahoma House Bill 1775, but opponents argue it will cast this teaching in a new light.

In May 2021, Kevin Stitt, the Republican Governor of Oklahoma, signed the bill into law. HB 1775 essentially prohibits teaching critical race theory — which explores racism’s impact on society — in Oklahoma schools, and restricts lessons that “an individual, by virtue of his or her race or sex, is inherently racist, sexist or oppressive.”

Some proponents of the bill in the Oklahoma House of Representatives and in the education system cited the importance of keeping leftist teaching out of schools.

Those opposed, including the Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission, said it could oversimplify lessons on complicated history. A clause in the bill states that teachers cannot include lessons that suggest “an individual, by virtue of their race or sex, bears responsibility for actions committed in the past by other members of the same race or sex.” Teachers are encouraged to teach events in a historical sense, but opponents say this will minimize the effects of the Massacre that people still feel today in favor of white students’ comfort.

“American and Oklahoma history is uncomfortable; and reconciliation requires truth and processing that is not comfortable,” Phil Armstrong, project director for Greenwood Rising History Center, wrote in a letter to Stitt. “Our entire mission and work is centered in this necessary discomfort.”

The timing of the bill was also a problem for opponents, who said passing a bill limiting teachers’ discretion on their lessons about racist history nearing the 100-year anniversary of the Massacre sets a bad precedent.

2021 not only marked 100 years since the Massacre, but it also marked a time where a concentrated focus was on racism in America. Following the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, Bennie says he noticed a big shift in Americans’ willingness to discuss the Massacre and other traumatic events for Black Americans.

“There’s been so much dirt hidden under the carpet,” Bennie says. “It shouldn’t have taken this long to talk about it.”

The organization Justice for Greenwood was founded in 2020. It aims to share information and advocate for those affected by the Massacre. It’s a nonprofit organization based in Tulsa that states its mission with three R’s: Respect, Reparations and Repair for the Greenwood community.

Reparations programs acknowledge that human rights violations in the past have caused lasting harm and attempt to provide money and other resources to people experiencing those harms in the present. These programs have been effective at increasing faith in the government, providing closure and emotional relief and alleviating economic hardships for Japanese Americans who survived World War II internment camps, according to a study by University of Michigan professors Donna Nagata and Yuzuru Takeshita.

Justice for Greenwood put resources toward a lawsuit filed by 11 people affected by the Massacre, including the last three known living survivors of the attack, against the City of Tulsa and other Tulsa organizations demanding accountability and restitution for the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre and 100 years of continued harm, according to the organization’s website.

Bennie says he started receiving emails from Justice for Greenwood shortly after the murder of George Floyd and the eruption of Black Lives Matter activism. These emails come almost daily and have persisted over the years. Before Justice for Greenwood, Bennie says nobody tried to contact him about his connection nearly as adamantly.

DJ Mercer, a lawyer on the plaintiff’s side of the case, contacted Bennie and many others with family history connected to the Massacre. The testimonies of people like Bennie helped Mercer make the case for reparations.

The case was dismissed in July 2022, but Justice for Greenwood is still fighting.

While Justice For Greenwood was fighting for reparations and the state of Oklahoma passed limitations on education about the Tulsa Race Massacre, Oregon made its own attempt at providing reparations.

In 2021, the Oregon Senate passed Senate Joint Memorial 4, which acknowledged the racist history of the state and the nation and stated “that we, the members of the Eighty-first Legislative Assembly, recognize the need to pursue avenues to implement reparations for the descendants of African slaves in the United States.” It urged those in national power, including the US Congress and the President, to take steps towards establishing reparations programs.

This bill came in response to Oregon’s deep history of anti-Blackness. Oregon passed its first exclusionary law in 1844, when it was still a territory and not yet a state. While the law banned slavery, it also excluded Black people from living in Oregon territory for more than three years, with violent consequences for violation.

In 1849, Oregon passed another law stating that no Black Americans not already living in Oregon territory could enter.

When Oregon became a state in 1859, its state constitution continued this precedent. It enshrined that no Black people “shall come, reside or be within this state or hold any real estate, or make any contracts, or maintain any suit therein,” according to section 35 of the Oregon state constitution’s bill of rights.

These laws were repealed in the early 1900s, but the presence of white supremacy remained strong. In 1923, the KKK claimed 35,000 active members, representing about 4% of the state’s population at the time. In contrast, according to the 1920 Oregon census, 14,243 Oregon residents were Black, representing less than 2% of the population.

Racist language was removed from Oregon’s constitution just over 20 years ago, in 2002, and to this day Oregon remains primarily white. According to the 2020 census, 74.8% of the state is “white alone” and 84.8% is “white alone or in combination.” Only 3.2% of the population is “Black or African American alone or in combination.”

Oregon tried to take the next steps on reparations in 2021 with Oregon Senate Bill 619. SB 619 states that "The Department of Revenue shall establish a program to pay reparations to Black Oregonians who can demonstrate heritage in slavery and who submit an application to the department," and "the department shall pay to each eligible applicant the amount of $123,000 in the form of an annuity payable annually for the life of the applicant."

SB 619 attempted to begin the process of providing reparations for those negatively affected by racism written into law, but in 2022, the bill stalled in the Senate. Like the effort from Justice for Greenwood, the bill was propelled by the events of 2020 but ultimately failed.

Oregon’s legislature will try again to establish a task force on reparations with Senate Bill 776, which was referred to the Ways and Means committee on March 24, 2023.

Regardless of where Bennie travels to share his story, there is some history of racism and harm that remains unaccounted for. Examples of reparations programs in America are few and far between, while examples of stories like Justice for Greenwood’s lawsuit and SB 619 are much more common.

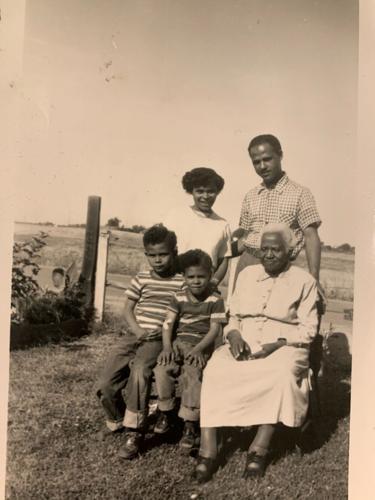

Bennie Jordan’s family poses for a photo in Oklahoma. Bennie’s grandmother, Josie, and his grandfather, James, are top left and top right, respectively. James was killed in the Tulsa Race Massacre in 1921, and Bennie is now older than his grandfather ever was.

Bennie is not confident that the efforts to provide restitution will affect his life meaningfully. It’s been over 100 years, and he’s not sure what restitution would look like. He is 66, and his life is already established, and he likes it. He is more hopeful for his daughter, who is younger and grew up with much more information than Bennie did about the Jordan family’s past.

“You have to share information,” he says, or it just might get lost.